Physical Address

23,24,25 & 26, 2nd Floor, Software Technology Park India, Opp: Garware Stadium,MIDC, Chikalthana, Aurangabad, Maharashtra – 431001 India

Physical Address

23,24,25 & 26, 2nd Floor, Software Technology Park India, Opp: Garware Stadium,MIDC, Chikalthana, Aurangabad, Maharashtra – 431001 India

By Aayushi Sharma

According to a new report, ‘Asia in the Global Transition to Net Zero’ by the Asian Development Bank, the benefits of attaining net zero emissions could be worth five times the price of mitigation. Global initiatives to attain net zero greenhouse gas emissions can have a significant positive impact on the economy and society.

Asia in the Global Transition to Net Zero examines the potential implications of a worldwide net-zero transition for developing Asia. The Paris Agreement’s obligations and pledges are used to simulate emission trajectories, which are then contrasted with more ideal paths to net zero emissions. The report finds that early action and international coordination are critical to ensure a low-cost and equitable net-zero transition. With efficient policies, the benefits of the transition from averted climate damages and improved air quality could outweigh climate mitigation costs by five times.

What are the key highlights for India?

As per the report, South Asia comprises Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

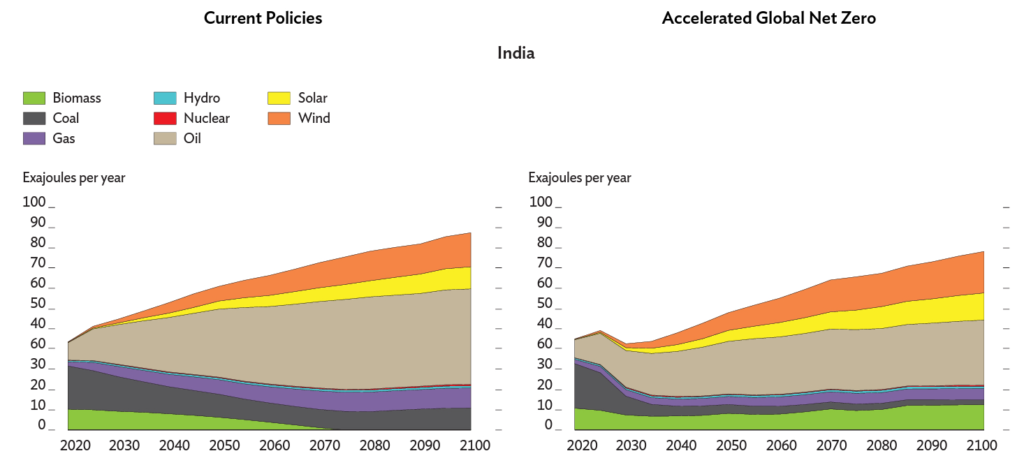

The graphs from the report show the need for India to reduce primary energy demand and switch to greener sources to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

What are some sectoral vulnerabilities Asia is facing?

The socioeconomic and geographic characteristics of developing Asia make it susceptible to hazards from climate change. As a result of climate change, the area will experience storms, flooding, heat waves, and droughts more frequently and with greater severity. Asia is home to around 70% of the world’s population that is vulnerable to sea level rise. About one-third of all jobs in the region are in industries reliant on natural resources, such as agriculture and fisheries, which are strongly influenced by the climate. Climate change may endanger not just the poor people of Asia but also regional and global food security.

The populations in developing Asia are the most susceptible to climate change globally. The average global temperature had risen faster than at any time in recorded history by 2020, reaching 1.1°C above preindustrial levels. Geographical and socioeconomic factors in the area put a large portion of the population at risk for climate-related dangers and pressures, and the region’s slow economic development limits the ability of billions of people to adapt. If climate change is not controlled, factors like rising temperatures, more frequent heatwaves and major storms, more unpredictable precipitation levels, and sea level rise (SLR) will limit the region’s development more and more. A failure to address climate change will result in significant economic losses for developing Asia.

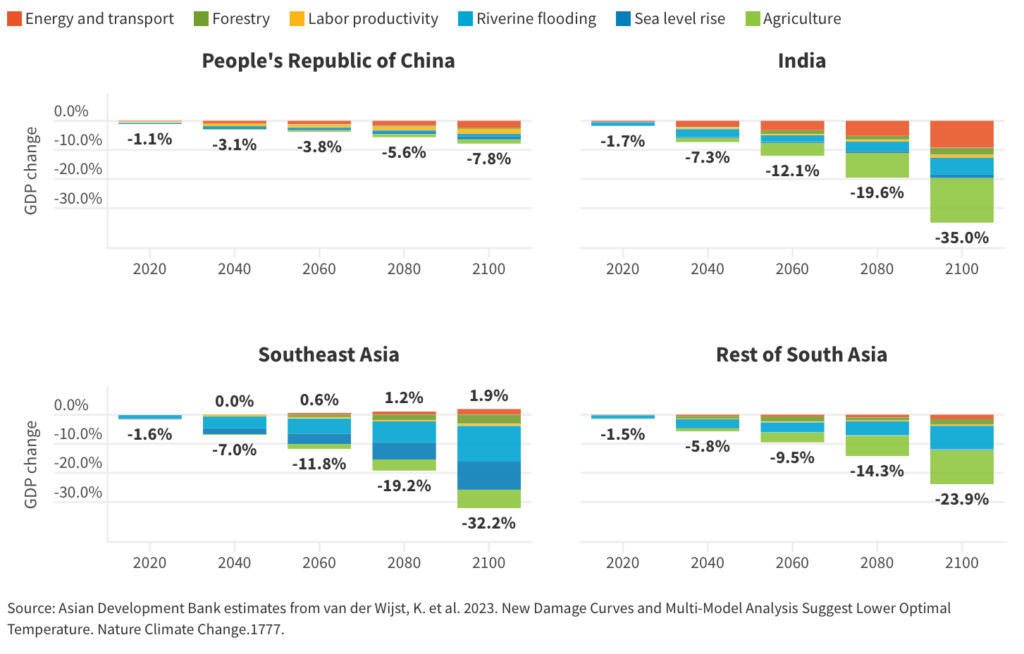

Projected economic losses in different regions of Asia due to Climate Change

By 2100, developing Asia stands to lose 24% of its GDP, according to evaluated estimates under the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) ‘s high emissions climate scenario. By 2100, India and Southeast Asia will have had mean GDP losses of 35% and 32%, respectively, while the rest of South Asia will have suffered losses of 24% and the PRC losses of 8%. It should be emphasized that these losses are significantly more than those anticipated by prior attempts to estimate losses under process-based modeling, which typically have indicated losses under comparable scenarios of less than 15% of GDP for subregions of Asia. Improvements in the way sector shocks have been analyzed directly contribute to the larger losses.

The following graphs show projected economic losses in different regions of Asia due to Climate Change.

A third of all jobs in the developing Asia region are in industries reliant on natural resources, such as agriculture and fishing, which are directly influenced by the climate. Increasing crop harvesting times, deteriorating yields and product quality, an uptick in pest and disease incidence, changing precipitation patterns, droughts, heat stress, flooding, saline intrusion, and SLR all affect agriculture productivity. Given that Asia accounted for 67% of world agricultural production in 2014, climate change may endanger not only the livelihoods of the region’s impoverished but also regional and global food security.

How will climate change impact the tourism industry in Asia?

A considerable number of people in Asia have occupations thanks to tourism, which has employment shares of 7.4% in Thailand and 11.5% in the Philippines (ILO 2021). As a result of climate change, Asia may spend more months in temperatures that aren’t suitable for travel. This might lead to losses of up to 40% in tourism income in the warmer countries of the region, notably the Philippines. These losses may be amplified by the frequency of extreme weather conditions as well as the effects of climate change on ecotourism hotspots like coral reefs and tropical forests.

How is Climate Change increasing Asia’s energy demand?

The rise in energy required for cooling is much more than the decrease in energy demand for heating, which may normally decline with climatic change. According to one prediction, annual cooling demand in regions of Asia in the 2050s may equal up to 75% of current electricity demand. In addition, when temperatures rise, thermal energy production becomes less efficient, hydropower may be negatively impacted by changes in surface fluxes and evaporation, and increasing storm activity may harm the infrastructure for transmission and distribution.

Is climate change reducing Asia’s labor productivity?

The report also highlights ILO’s finding that Developing Asia has peak humidity–adjusted temperatures that are at the upper limits of the conditions permitting physical labor. Agriculture and other industries that are difficult to cool will suffer significant output losses due to climate change. By 2030, there might be a loss of 3.1% of working hours as a result of these restrictions being surpassed for considerably longer periods of time due to climate change.

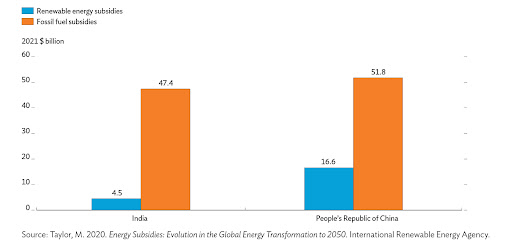

Fossil fuel subsidies in developing Asia totaled $116 billion in 2021. These subsidies are far greater than those for renewable energy sources. At close to 1% of GDP, the cost of fossil fuel subsidies is comparable to the policy cost of this report’s most aggressive decarbonization scenario. Artificially low costs encourage excessive use of fossil fuels and impede the growth of renewable energy sources. Similar incentives for emissions from deforestation are created through concessions that allow for subsidized timber extraction, and subsidies for agricultural inputs frequently encourage excessive use of emission-intensive inputs.

The first step towards low-carbon growth and the redistribution of precious public resources for other development objectives needs to be the elimination of these subsidies.

References: