Physical Address

23,24,25 & 26, 2nd Floor, Software Technology Park India, Opp: Garware Stadium,MIDC, Chikalthana, Aurangabad, Maharashtra – 431001 India

Physical Address

23,24,25 & 26, 2nd Floor, Software Technology Park India, Opp: Garware Stadium,MIDC, Chikalthana, Aurangabad, Maharashtra – 431001 India

Every year April 22 is celebrated globally as Earth Day, a day meant to inspire people to get involved, mindful of issues plaguing our mother Earth so that they can pledge their support for the planet. This year Earth Day’s theme is “Invest in our Planet”. It calls on the people to get together in building a healthier economy while making sure that it is done in a way that the future is equitable for everyone.

Thus, on the occasion of Earth Day, Climate Fact Checks (CFC, India) has decided to showcase major environmental movements and conservation methods taken by some of the Indian indigenous groups and communities. Their unique way to protect and conserve nature always fascinates us and we salute them.

In many parts of the world, tribal communities have been essential to ecosystem management. Over the years, they have created a strong cultural bondage with nature. The most intriguing characteristic of these indigenous people is that they reside in regions that are extraordinarily rich in biodiversity. It is believed that there are 300 million indigenous people living worldwide, and 150 million of them live in Asia.

About 9% of Indians live in tribal communities, the majority of which are concentrated in Central India. The majority of tribal communities revere nature. They respect the mountains, rivers, rocks, and forests. They hold a belief in spirits that exist in nature and their natural surroundings and may be good or bad depending on what is best for their existence and livelihood. The level of emphasis accorded to the environment is immense; in fact, they worship natural items while elevating the environment to the rank of a deity. Because they hold the belief that their ancestors lived in nature and were housed in natural items, they even maintain the environment out of a sense of responsibility to them.

These groups have amassed indigenous knowledge about farming and coexisting in ways that don’t significantly affect the forest ecosystems. By using sustainable methods for farming, fishing, and coexisting with animals, Indian tribes have contributed to preserving natural environments for generations and helped advance conservation.

For instance, the Apatani tribes are well-known for their environmentally friendly wet rice farming methods in regions like the Ziro Valley, where nutrients wash down from the hilltops to support crop growth. Similar to this, indigenous animal species like the Himalayan squirrel are safeguarded through a system known as “Dapo,” in which the head of the community establishes guidelines for hunting and collecting animals that, if disregarded, can result in penalties. The ethnomedical herbs in the Sirohi district are reportedly well-known to the Garasia tribes.

Tribes frequently use totems and religious principles that forbid the eradication of specific animals and plants when it comes to protecting wildlife. For instance, tigers, sparrows, and pangolins are not hunted since they are seen to be good luck charms for humans by the Adi tribes of Arunachal Pradesh. The removal of banyan trees is thought to cause famine and mortality as well. In the end, this promotes the preservation of species. The tribe of Akas in Arunachal Pradesh reveres Mount Vojo Phu as a holy peak. Because of this, there are restrictions on how people can access the mountain in an effort to protect the native flora and animals.

In terms of farming methods, the Kadars of Tamil Nadu only remove fruits and vegetables from fully developed plant stems, which are then trimmed and replanted for future harvest. A mixed cropping strategy, used by the Irulas, Muthuvas, and Malayalis farms, involves growing a variety of crops in one location at the same time. Since various crops have distinct nutritional needs, this also minimizes soil erosion and over-exploitation of the water table and soil nutrients. Madhya Pradesh’s Gond, Pradhan, and Baiga groups use Utera farming, which involves sowing subsequent crops in paddy fields before the main crop is harvested in order to take advantage of the soil’s remaining moisture before the land dries up. These villages also practice the Badi cropping method, in which fruit trees and crops are grown along the edge to act as a buffer against droughts and torrential downpours and to avoid soil erosion. Nutrient cycling and soil fertility are made possible by mulching, burning leaves for residue, and keeping roots and stumps.

Bishnoi: The first environmentalists of India

One of the earliest groups in India to formally advocate for environmental preservation, animal welfare, and sustainable living was the Bishnoi movement. The Bishnois are credited with being India’s earliest environmentalists.

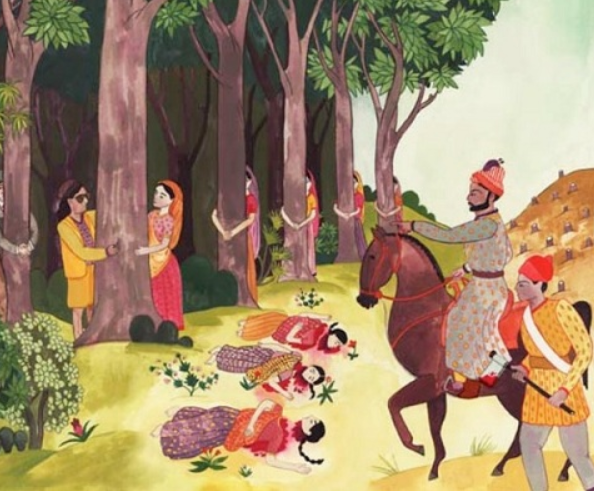

The Bishnoi Movement: The well-known Amrita Devi movement is regarded as one of the first initiatives for environmental protection. This movement hugged and embraced trees in an effort to safeguard them. Bishnoi from Khejarli and nearby villages joined the protest and hugged each Khejri tree individually to show their support for the trees from being cut down at the expense of their lives. 363 Bishnois gave their lives in this movement to defend the Khejri trees in the Rajasthani village of Khejarli.

The Bishnois’ love of nature has enabled them to endure Thar Desert droughts. Additionally, it has assisted in protecting local wildlife from poachers. The gorgeous Black Buck was listed on Schedule-I of the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 before the Bishnoi community started doing this. Before the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 was created, the Bishnois lived there. This demonstrates that they have an innate knowledge and believe that they exist because of nature. They take it as their responsibility to protect the environment.

People of the Bishnoi Community feed water to a sick fawn near Jodhpur, Rajasthan

Bhil: The Bowmens and their Soya system of forest management

The Udaipur district is located southwest of the Aravalli highlands in southern Rajasthan. The hills in the Udaipur district supply numerous rivers and are home to a diverse range of wildlife; 43% of the territory is covered by forests. The Bhil and Garasiya tribes as well as other Bhil subclans call it home. They make up around 60% of the district’s population. The ‘bowmen of Rajasthan’ are Bhils, who live in this region of Rajasthan. They had a reputation for being excellent hunters who valued local autonomy.

Bhil community can be located in the Aravalli Ranges of Sirohi in Udaipur and the Dungarpur and Banswara districts of Rajasthan

The ‘Soya’ system is another notable aspect of the native approaches to forest management. It suggests that every home has a responsibility to participate in keeping watch over its forest as a guard. As a result, each home will keep an eye on the forest for a day, and with the start of a new day, the duty will pass to the next neighbour. The entire village also takes part in this stewardship responsibility. Passing the “baton,” which each member carries when they watch the forest, is a ceremony that binds the members of this trusteeship. He or she hands the baton to the neighbour after finishing up their duties for the day.

The phrase “the forest is ours, and we are conserving our future” used by a villager, accurately captures the symbiotic relationship between the forest (nature) and humans.

Kodbahal: A place where locals pet deer

Kodbahal, a village in Sundargarh District’s Hemgiri Forest Range, has gained recognition as a sensitive village to conservation because of the community’s long-term commitment to preserving the local deer population. This forest region is renowned for its wide, natural woodland that is verdant and lush and contains old caves and rock carvings. This range is covered in dry peninsular Sal and dry mixed deciduous forests with bamboo breaks.

Ganda, Bhuyan, Kishan, Oram, Munda, and Khadia are the main forest-dwelling communities that have access to this range. The Kodbahal community is unique in that it is interested in the preservation of the forest and the protection of the spotted deer (Cervus axis). The inhabitants belong to the Dehuri tribe, a sub-group of Gondo-Bhuyan; they believe that the local deity adores wild animals and that they should not be harmed. This conviction has motivated them to protect the spotted deer population on 200 hectares of mixed forest.

The regenerating forest provided sufficient habitat for deer and other wild animals, and residents patrolled them on a regular basis. Deer depredation of crops is frequent in this village, where agriculture is the primary source of income. Deer are not afraid to enter human dwellings and raid crops in backyard gardens. Villagers are used to seeing herds of deer roaming around their neighborhoods. The villagers, on the other hand, seek formal acknowledgment in order to increase their efforts and protect the creatures they adore and appreciate.

Chenchus: Sacrifice their life for the Nallamala forest

The Chenchu are a hill tribe that largely inhabits the state of Andhra Pradesh in southern India. They primarily live in the higher peaks of the Amrabad Plateau, which is covered in clean, deep woods. There are further Chenchu communities in the states of Orissa, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. Their native language (also called Chenchu) belongs to the Dravidian language family. Many also speak Telugu, the language of their Hindu neighbors.

The Chenchu community has gained the title “Children for the forest” as they are an integral part of India’s largest tiger reserve- Nagarjunasagar Srisailam Tiger Reserve (NSTR). Although the forest department’s frontline workers are steadfastly dedicated to the preservation of this tiger reserve, the department also recognizes that the local Chenchu community’s support of tiger protection is a significant factor in the tiger population growth. The landscape of NSTR- the Nallamala hills are better known by Chenchu, therefore the Chenchu have been employed as protection watchers in the basecamps by the forest department of the government of Andhra Pradesh.

Members of the Chenchu tribe keep vigil and prevent trespassers

A protection watcher’s normal day is patrolling the forest, noting any animal activity or its evidence (such as scat), inspecting all vulnerable routes and the specified patrolling paths, and keeping an eye on water sources. While the Chenchu men patrol the forests, the women protect their hamlets by ensuring the safety of their forest and all the creatures that depend on it for survival.

Protest of Chenchus against Uranium Mining

Recently the community has gained much attention for protesting against the proposal of mining uranium that will eventually abrupt the biodiversity. The Chenchus are renowned for their kinship with animals and comprehension of nature. The Chenchus have been compelled to act on their own because the state government has not enforced the law. For that, they have strengthened their tribal territories as the best line of control of the forest. Lachamma, a Chenchu woman said “We know it’s risky and we have enemies. But now’s no time to hide. We are ready to die protecting this forest but will never let anyone take control of our lives”

Apatani Community: Tribe with a unique style of farming

An Indian ethnic community called the Apatani, or Tanw, also called Apa and Apa Tani, resides in the Ziro Valley of the Lower Subansiri district of the state of Arunachal Pradesh. They are the largest ethnic group in the eastern Himalayas and practice a unique style of agriculture that combines the cultivation of rice and fish. Since the 1960s, these farmers have been engaged in integrated rice-fish farming on their mountain terraces in the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. Integrated farming here refers to a system of producing fish in combination with rice farming operations centered around the fish pond.

The Apatani plateau’s Napping, Yachuli, Ziro-II, Palin, and Koloriang are prospective locations for rice-fish farming. Emeo, Pyape, and Mypia are the three rice kinds most commonly used by Apatanis. There are several different civilizations in the Apatani Plateau. The Apatani plateau gets enough rain during the summer. This unusual agricultural method is favored by the clayey, loamy soil’s permeability and propensity to hold water.

They also practice low-input, environmentally benign methods of integrated rice-fish agriculture. Farmers virtually ever need to apply additional fish feeds because the stocked fish largely rely on the natural food sources of the rice fields. Water from the networks of earthen irrigation channels is dispersed using bamboo pipes and two outlet pipes. In order to maintain the water level, one outlet is installed angularly via a dyke, and another outlet is installed to the exterior at the bottom of the dyke. During harvest, it is used to dewater the field. While preparing the land for rice cultivation, men and women carry out various farm tasks. And women make up the majority of the workers in the fish culture.

Devban: Nexus of Traditions and Modernity

Devbans are isolated areas of wilderness in Himachal Pradesh that are revered as holy and the property of regional deities. These land patches frequently encircle the temple or the Devta’s residence. Depending on the social significance and the Devta’s position in the hierarchy of Devtas, these lands are typically rich in biodiversity and range in size. These areas of land are known as sacred groves or forests.

In terms of ecological and social legacy, sacred grooves serve as a link between modern civilization and past civilization. They are regarded as one of the finest examples of conventional methods for managing biodiversity.

The Devban of Parashar Rishi Devta in Mandi district is one such example of the sacred grove. Folklore holds that the temple, which served as the Devta’s home, was built from a single Deodar tree,thusDeodar tree gains a special status among the other profane plant and tree species in the ecosystem as a result of its use in the creation of this sacred location.

The members of the dominant caste Rajput community maintain the Devban of Parashar Rishi, which is full of Deodar trees. Although the government has assumed control, residents claim that nobody ever has the audacity to steal Deodar wood from the Devta’s Devban, therefore it doesn’t really matter. Additionally, the government takes the necessary steps to safeguard the forest, and they are of the opinion that The Devban is safe since no one wants to face the vicious anger of their Devta. Therefore, it can be stated that efforts taken to protect sacred trees are motivated by fear of facing a deity’s wrath.

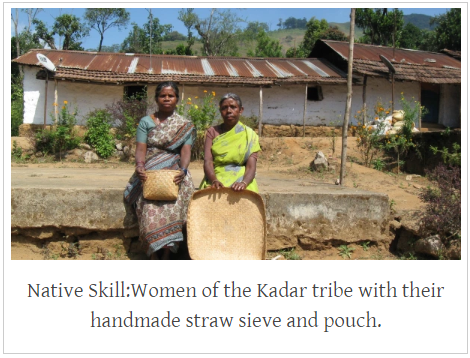

Kadar: primitive tribe to protect hornbills

The Keralan districts of Palakkad and Thrissur are home to the “primitive tribe” known as the Kadars. Kadar is the Malayalam word for “forest dwellers”. The tribe used to lead a nomadic lifestyle and engage in shifting cultivation, where they grew millets and rice. In addition, they pursued tiny animals and birds, especially hornbills.

Athirappilly-Vazhachal-Nelliyampathy forests in the southern Western Ghats is the only region where all four south Indian species of hornbills (the great Indian hornbill (Buceros bicornis), Malabar pied hornbill (Anthracoceros coronatus), Indian grey hornbill (Ocyceros birostris) and Malabar grey hornbill (Ocyceros griseus)) are found. Kadar community used to poach them for their meat and gathered their eggs to add to herbal mixtures with dubious medical properties. In the last two decades, the practice has fully ceased, and now they are tasked with maintaining the safety of the birds and their nests.

Years back, Gramasabhas- the customary village assemblies of Kadar, had issued resolutions opposing the divisive Athirappilly hydroelectric project in their area. In addition to doing irreversible harm to the local community’s concerns for its way of life, the 23-meter high dam was predicted to drown 104 hectares of forest area which will affect 196 bird species, 131 butterfly species, and 51 odonate species. The critically endangered Malabar pied hornbills have no other breeding locations in Kerala other than this. The implementation of this project will affect the hornbill population as they have unique habitats.

72 Kadar youth along with joint efforts of the Western Ghats Hornbill Foundation (WGHF) and Kerala Forest Department took initiatives to safeguard the hornbill habitat. The youngsters keep a close eye out for poaching by assisting the forest department in stopping the illegal felling of nesting trees and discouraging other young people from their community from joining poaching networks. Through tree planting and wildfire suppression efforts, they improve the forest habitat. Additionally, they make sure there is little human disturbance in these areas during the nesting season, which typically starts in December. Through long-term efforts, the Hornbills population has increased significantly.

The WGHF and the Kadar youth are now concentrating on creating a mechanism for long-term monitoring of the rainforest ecology in addition to hornbill conservation. Observing the changes in bird breeding, changes in habitat, and the effects of deforestation by utilising the traditional knowledge and effectiveness of the Kadar youths are some of their objectives. Through all these initiatives, they are creating a long-term monitoring system to evaluate changes in the rainforest, which is essential for upcoming conservation efforts.

The traditional environmental knowledge of the tribal peoples is extremely helpful in creating site-specific strategies for the protection of biodiversities as well as in constructing mitigation plans for dealing with climate change and sustaining their way of life. They created several regulatory mechanisms to enable them to protect the natural world, which they viewed as their mother, the resting place of their ancestors, the home of the deity, or a sacred site.

Source:

https://www.fao.org/3/xii/0186-a1.htm

https://www.youthkiawaaz.com/2018/11/the-forest-is-ours-and-we-are-conserving-our-future/

https://magazines.odisha.gov.in/Orissareview/2022/Nov/engpdf/18-28.pdf

http://cpreecenvis.nic.in/Database/TraditionsofAnimalConservationinOdisha_3686.aspx