Physical Address

23,24,25 & 26, 2nd Floor, Software Technology Park India, Opp: Garware Stadium,MIDC, Chikalthana, Aurangabad, Maharashtra – 431001 India

Physical Address

23,24,25 & 26, 2nd Floor, Software Technology Park India, Opp: Garware Stadium,MIDC, Chikalthana, Aurangabad, Maharashtra – 431001 India

What are Alien and Invasive Plants?

Invasive alien plant species (IAS) are introduced into places outside their natural range, negatively impacting native biodiversity, ecosystem services or human well-being. They are non-native to an ecosystem and may cause economic or environmental harm. They impact negatively on biodiversity, including the decline or elimination of indigenous species through competition for water and the disruption of local ecosystems and ecosystem functions. Without natural enemies, these plants reproduce and spread quickly, taking valuable water and space from our indigenous plants. Many alien plants consume more water than local plants, depleting our valuable water resources.

During the last few centuries, however, people started moving over large distances at an accelerating pace and shipping a larger volume of commodities to faraway destinations. This ever-increasing massive and rapid movement of people and goods has facilitated the transport of various plants, animals, and organisms to completely new, non-indigenous environments. Upon encountering unique ecosystems, many of these intentionally or accidentally brought organisms may perish, unable to survive in foreign environmental conditions. Some of them may be able to survive only if they are deliberately cultivated. Finally, some will become invasive, establishing their presence and spreading over a non-native environment.

Climate Change and Alien Invasive Plants

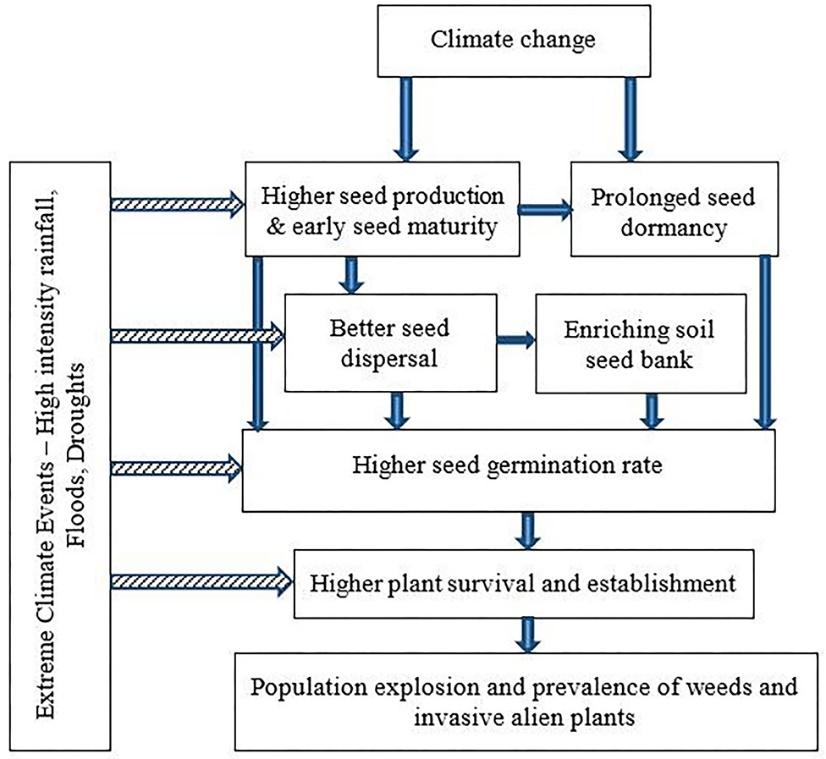

Both climate change and invasive species pose extraordinary ecological challenges to the world today. Climate change and rising average world temperatures can profoundly influence species’ geographical ranges, often set primarily by climate and, consequently, the host environment. Climate change facilitates the spread and establishment of many alien species and creates new opportunities for them to become invasive. IAS can reduce the resilience of natural habitats, agricultural systems and urban areas to climate change. Conversely, climate change reduces the strength of habitats to biological invasions.

There are a few possible scenarios of the climate change impact on pathways and destinations. From one point of view, it can become a limiting factor. Increased variability of extreme climatic events can potentially hinder the exports of agricultural goods that won’t be able to produce expected yields due to extreme climatic events like drought or flooding. Overpopulation and water shortages can disrupt the fragile balance of food supplies. In that sense, climate change can hurt the pathways and decrease the risk of the interception of invasive species in different countries. From another perspective, extreme events will likely increase the number of migrating climate refugees.

Sri Lanka and Invasive Plants

Internal trade, aid, travel and transportation have helped the movement of IAPs into natural and artificial ecosystems in Sri Lanka. The country occupying a land area of 62,707 km² and water bodies of 2,905 km² is an island nation with a physically diverse geography and tropical climate. Sri Lanka is a Biological hotspot of many native species. Sri Lanka is one of the 35 global biodiversity hotspots. According to the National Red List (2012), Sri Lanka is home to about 750 vertebrates, 1500 invertebrates, 3,150 flowering plants, 336 Pteridophytes (ferns) species, 240 birds, 211 reptiles, 245 butterfly species and 250 land snail species. Due to the rich coastal and marine biodiversity, there exists about 208 species of hard coral, 750 species of marine molluscs, and over 1,300 species of marine fish, supported by ecosystems such as coral reefs, mangroves, sea grass beds, salt marshes, dunes and beaches. However, Sri Lanka’s unique biodiversity is currently in decline. Statistics state that of the species found in Sri Lanka, 27% of birds, 66% of amphibian species, 56% of mammals, 49% of freshwater fish species and 59% of reptiles and 44% of flowering plant species are threatened.

These invasive species are found in the dry zone, low country wet zone, upcountry dry zone and island-wide and have been observed spread in tanks, reservoirs, marshes, streams, forests, grasslands and barren land.

At present, alien invasive plant species have spread all over the island of Sri Lanka, of which 20 plant species have been identified as the top 20 most invasive species, whilst 15 species have been identified as potentially invasive. The invasion of agricultural lands by the spread of these plants leads to numerous issues, thus affecting food production and quality, depleting water capacity, causing water pollution, disrupting the balance of biodiversity, causing the disappearance of beneficial plants, affecting soil fertility, and causing forest fires in parks due to Ginithana.

Some plants introduced to Sri Lanka have become noxious weeds or invasive plants. The Royal Botanic Gardens, Peradeniya, played a significant role in many such introductions.

A brief history examples of the invasive alien species in Sri Lanka :

The below table shows some Invasive alien flora introduced through botanic gardens.

| Family | Species | Country of origin | Year of introduction |

| Asteraceae | Ageratina riparia | Mexico | 1905 |

| Asteraceae | Tithonia diversifalia | Mexico | 1851 |

| Clusiaceae | Clusia rosea | West Indies | 1866 |

| Dilleniaceae | Dillenia sujfruticosa | Borneo | 1882 |

| Fabaceae | Myroxrylon balsamum | Venezuela | 1870 |

| Fabaceae | Prosopis juliflora | Tropical America | 1880 |

| Fabaceae | U lex europaeus | Europe | 1888 |

| Iridaceae | Aristea ecologic | Guatemala | 1889 |

| Melastomataceae | Clidemia hirta | Tropical America | 1894 |

| Melastomataceae | Miconia calvescens | Mexico | 1888 |

| Polygonaceae | Antigonon leptopus | Tropical America | 1870 |

| Pontederiaceae | Eichhornia crassipes | Hong Kong | 1905 |

| Solanaceae | Cestrum aurantiacum | Cape of Good Hope | 1889 |

| Lantana camara | Lantana camara | Tropical America | 1826 |

Can get more information here

As Sri Lanka is an island with sensitive ecosystems with unique biodiversity, it is essential to conserve biological resources against biological invasions. Quick action is vital in controlling and managing invasive alien species as it is convenient and cost-effective when the age of introduction and area of spread is small. The necessary action taken to prevent the spread and distribution of Parthenium and Alligator weeds and Mimosa pigra by the Departments of Agriculture and Irrigation in recent years was very successful because the plants were eradicated within limits of control.

The threats of IAS cannot be treated in isolation but are part of a complex set of pressures and drivers of biodiversity loss and environmental change. The social, political and economic drivers in Sri Lanka are growing in scale and scope. Therefore, the responses to IAS need to go beyond short-term crisis-focused approaches. They need to be at multiple levels, and, in many incidences, an interlinked process that considers the horizontal linkages between environmental sectors and the links between development and social objectives will need to be adopted. Plant Protection Act No. 35 of 1999 has been introduced to deal with invasive plants in Sri Lanka, and the Plant Protection Service of the Department of Agriculture is functioning as the implementing authority. Accordingly, the main objective of the Plant Protection Service is to identify the organisms that are harmful or destructive to the plants in Sri Lanka, prevent them from spreading and preserve the health of the plants in Sri Lanka.

How does climate change help alien plant species grow in eastern Sri Lanka?

Climate changes have worsened the problems caused by weeds and invasive alien plants (IAPs) in agroecosystems globally, resulting from their differences in the range and population densities. Over the past six decades, Sri Lanka has experienced a slow but steady increase in annual environmental temperature by 0.01–0.03°C. Increasing extreme events of rainfall, wetter wet seasons, and drier dry seasons are some of the characteristic features of the changes in the climate observed in Sri Lanka over the years. The Ministry of Environment (MOE) in Sri Lanka established a National Invasive Species Specialist Group (NISSG) in 2012. It adopted the National Policy on Invasive Alien Species (IAS) in Sri Lanka, Strategies and Action Plan 2016.

The efforts to identify biological invasions and predict their impacts on ecosystems under changing climate have yielded inconsistent results. Some studies have reported that the current distribution of IAPs may not be in equilibrium with the current environment, nor that their potential establishment and spread be determined primarily by climate. Here. Archived.

The IAPs have been reported to adapt to climate change showing plasticity in their growth pattern. For example, Bromus tectorum has shortened its life span under drought conditions and extended its root system to deeper soil layers, thus, demonstrating better adaptation of IAPs compared to most of the

IAS reduce the resilience of natural habitats, making them more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. For example, some grasses and trees that have become IAS can significantly alter fire regimes, especially in areas that are becoming warmer and drier. This increases the frequency and severity of wildfires and puts habitats, urban areas and human life at risk. IAS can also impact agricultural systems by reducing crop and animal-healthy native plant species. The invasive alien species.

Control and Management Activity in Sri Lanka

In 2007 (MENR, 2007), as a part of the Addendum to the Biodiversity Conservation in Sri Lanka – a framework for action, the Ministry of Environment (ME) of Sri Lanka proposed to formulate a National Action Plan for the Control of IAS in protected areas. A National Invasive Species Specialist Group (NISSG) has also been proposed to be appointed to deal with the issues related to alien invasions. The Biodiversity Secretariat of the ME has conducted many awareness programmes to educate the general public on the adverse impacts of IAS. One-year project on managing aquatic weeds in 2005/2006, with funding from the FAO. This project involved awareness-raising activities and pilot scale control programmes targeting S. molesta, E. crassipes and P. stratiotes—the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWLC). The DOA is also rearing the Neochetina eichhorniae and N. bruchi bio-control agents and releasing the organisms to control E. crassipes. Recently, the DOA launched a chemical control programme for E. crassipes in the northwestern province in collaboration with the Irrigation Department. The DOA, ME, universities and other governmental, non-governmental and private organisations are actively involved in programmes to control P. hysterophorus. The government of Sri Lanka released an extraordinary gazette notification in December 2000.

If you have any queries or come across suspicious content related to climate change or the environment and want us to verify them for you, then send them to us on our WhatsApp hotline: +917045366366

-With Inputs from Dinesh Balasiri–