Physical Address

23,24,25 & 26, 2nd Floor, Software Technology Park India, Opp: Garware Stadium,MIDC, Chikalthana, Aurangabad, Maharashtra – 431001 India

Physical Address

23,24,25 & 26, 2nd Floor, Software Technology Park India, Opp: Garware Stadium,MIDC, Chikalthana, Aurangabad, Maharashtra – 431001 India

By Vivek Saini

Since the last two decades, there has been a severe water crisis in the Indian region of Bundelkhand. The central government, media, and academia have all paid close attention to this water situation. Although numerous laws and policies have been passed, a lot of resources have been distributed, there hasn’t been much progress made locally. Seasonal precipitation patterns, agricultural practices, and land use have all undergone significant changes as a result of climate change in the region. This article discusses such issues and their remedial measures that are being taken by the NGO and local community.

How locals had to suffer the water shortage

Kamlawati Yadav gets up at six in the morning every day in the heat to make the half-kilometer walk to a home with a personal borewell. Kamlawati declares, “Getting water is the first thing I do. I carry a second water jug by hand in addition to the one on my head. To collect the water her family of five needs, she will have to make the trek again in the evening, carrying 72 liters on each trip.

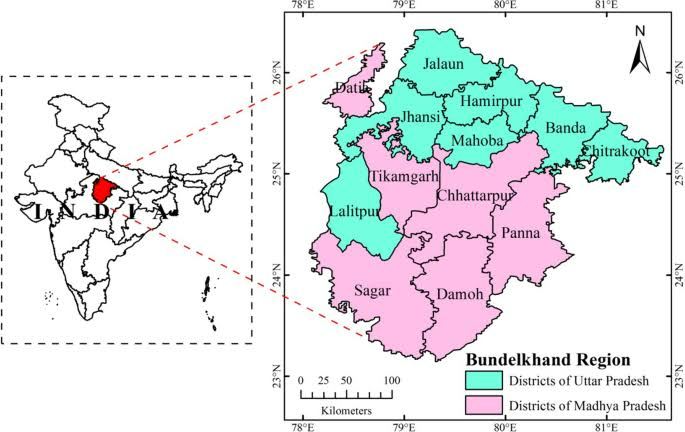

She moves the containers inside the house with the aid of her daughter, “We have to get things done with four buckets of water per day,” she explains. The Yadav family resides in Barua village, which is part of the Satna district of Bundelkhand, a mountainous and frequently dry region of central India that is shared by the states of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. In Bundelkhand, there are more than 18 million inhabitants.

Anil Gupta, division head of India’s National Institute of Disaster Management, said that in recent years “Bundelkhand has become a synonym for drought, unemployment, and perennial water stress.”

According to the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs of India, every person in rural regions ought to have access to 55 liters of water each day. With her four buckets, Kamlawati’s family of five can only get about 29 liters per person per day, which is less than half the minimal amount advised.

Image 1

How climate change affecting the water availability

Due to its fragile geophysical condition, the Bundelkhand region is extremely vulnerable to climate change. One of the least developed areas of the nation is made up of six districts in Madhya Pradesh and seven in Uttar Pradesh. By the end of this century, temperatures in the Bundelkhand region are anticipated to have risen by roughly 2-3.50C, according to UNITAR’s (United Nations Institute for Training and Research) climate tests.

In addition, the Bundelkhand region has experienced drought in successive years. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, there was a severe drought in the area every sixteen years. The region has had eight major droughts in the past fifteen years (2002, 2004, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2014, and 2015), and this frequency has grown.

Rainfall in Bundelkhand is shifting as a result of climate change, which is altering weather patterns. The region’s yearly rainfall decreased by 60% between 2013 and 2018. Geologists nevertheless came to the conclusion that the region’s typical rainfall should be sufficient in 2020. Water is scarce in Bundelkhand, however, because of “a variety of environmental factors, including rocky surface, high temperature, fast runoff of water, lowered groundwater table, and deforestation of the upper slopes,” the researchers noted.

Gunjan Mishra, an environmentalist from Chitrakoot, emphasizes mining and rock type as major concerns. Mining destroys the routes that allow water to trickle into subsurface aquifers. The stony topography exacerbates the issue, as rainwater runs off and does not recharge the groundwater.

“Lalitpur, Chitrakoot, Mahoba districts see no improvement in groundwater depletion [after the rains] because of the ongoing mining and hard rocks in the region. There are a few areas where farmers have built ponds [to store rainwater] but it helps increase the [groundwater] level only within a one-kilometer vicinity. So, we can say that the situation of underground water level has only deteriorated in the region,” he said.

Caste dominance makes things harder

Caste adds to the issues of geography and gender. “The family we visit for water has their own borewell, and they are gracious enough to provide us with four buckets per day. We used to get our water from another home, one kilometer away, before this. For four buckets of water, they started charging us 50 rupees [US $0.70] one day. However, they wouldn’t impose any fees on the Thakurs (members of a privileged caste)”, claims Kamlawati.

The other backward class group, one of the four broad socio-economic divisions in India’s official statistics, includes Kamlawati and her family. Only the final of these four groups—scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, other backward classes, and general category—is referred to as an “upper caste”.

Delinquent attitude towards traditional water harvesting system

Due to the presence of hard rocks in the Bundelkhand region, it is particularly challenging to explore the groundwater that occurs in the cracked and joined granite and gneiss. Additionally challenging is the region’s high rate of surface water evaporation loss.

Traditional water conservation methods are completely ignored in the Bundelkhand regions, and government planning gives them very little weight. It was discovered that the traditional water collection structures’ capacity was reduced by siltation as a result of insufficient maintenance. The spatial distribution of reservoirs is lessened by human encroachment on catchment areas and pond beds for commercial exploitation, including construction work on shopping centers and certain posh colonies.

Additionally, the misuse of water resources results in the degradation of water quality due to the development of various aquatic weeds within ponds, the waste of water from artesian wells, and alternative uses of tanks as garbage dumps, among other things.

Negligence at the policy-making level

In this area, it has been discovered that the management of local water resources and customs has been completely disregarded in the interest of development. Water crises are also brought on in this area by illogical and foolish policies relating to estuaries, mines, mountains, rivers, etc. for short-term financial gains. Before undertaking initiatives linked to highways, forests, and tube wells, insufficient scientific research was conducted. Changing crop patterns and declining agriculture necessitate using a lot of water for irrigation.

Groundwater is being used irrationally, and resource utilization lacks long-term eco-friendly planning. Massive deforestation, indiscriminate and unregulated mining, and growing urbanization are all occurring. Centralized water supply systems are placing an unfavorable pressure on the groundwater in the Bundelkhand region. The region’s soil salinity and brackishness have increased as a result of the construction of dams and canals. Water is wasted as a result of unregulated mining. The Bundelkhand region experiences numerous health issues as a result of water contamination.

Preventive measures that have been taken in the region

The Jal Saheli’s are in charge of advancing the water security agenda and acting as a collective voice for water rights & entitlements, including government programmes, through initiatives like awareness-raising. By doing this, Jal Saheli involves the local population in the construction of the village’s water system and the creation of a master plan for water users. Additionally, she works with the panchayat, the government, and politicians while bringing up water issues at the village level. Parmarth samaj sevi sansthan has first launched the Jal saheli cadre in April 2011 in 96 villages across three districts and has already selected over 1100 Jal sahelis throughout six districts.

The Parmarth Jal Saheli model is officially recognised as the best NGO model by the Union Government’s Ministry of Jal Shakti. Despite the region’s dry weather, Jal Sahelis have provided water to at least 100 Bundelkhand villages.

Image 2

Varsha Raikwar, a 25-year-old radio jockey from a tiny village in Madhya Pradesh, is increasing grassroots climate change awareness through community radio station Radio Bundelkhand. She assists in reaching the rural population with climate awareness messages through community-driven activities like seminars and street plays, and she explains the consequences of climate change through real-life changes that people have seen in their villages. For her, radio is an excellent medium for overcoming knowledge gaps, discussing the causes of the climate problem and campaigning for subjects such as health, education, women’s empowerment, and others.

References: