Physical Address

23,24,25 & 26, 2nd Floor, Software Technology Park India, Opp: Garware Stadium,MIDC, Chikalthana, Aurangabad, Maharashtra – 431001 India

Physical Address

23,24,25 & 26, 2nd Floor, Software Technology Park India, Opp: Garware Stadium,MIDC, Chikalthana, Aurangabad, Maharashtra – 431001 India

Many fail to connect the dots on how the impacts of climate change could aggravate the spread of many infectious diseases, particularly vector-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue. During the investigation of climate fact checks, we identified climate change as a leading factor in dengue vector distribution.

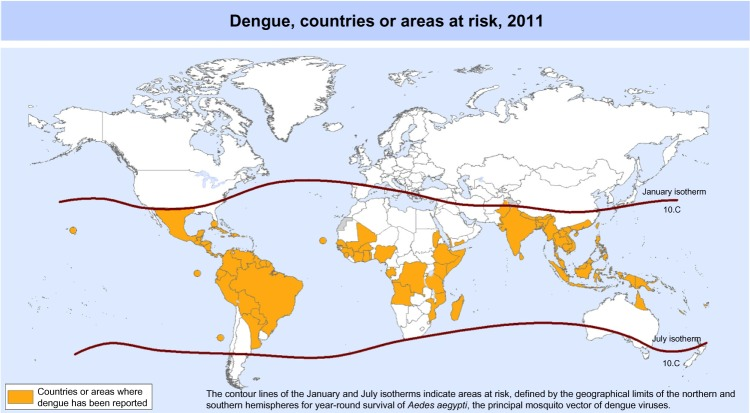

Dengue is a mosquito-borne viral disease that has rapidly spread in recent years. Dengue virus is transmitted by female mosquitoes, mainly of the species Aedes aegypti and, to a lesser extent, Ae. albopictus. These mosquitoes are also vectors of chikungunya, yellow fever, and Zika viruses. Dengue is widespread throughout the tropics, with local variations in risk influenced by climate parameters and social and environmental factors. The research and recommendations of the World Health Organization on the dengue virus can be read here Archived.

Here are our findings on climate change inducing dengue spread.

Temperature is one of the most critical environmental factors affecting the biological processes of mosquitoes, including their interactions with viruses. Rates of dissemination were higher at 25°C and remained that way even at 30°C relative to adult mosquitos. Additionally, a study shows that generation interval is highly sensitive to temperature, decreasing twofold between 25 and 35°C. This suggests that dengue virus epidemics may accelerate as temperatures increase, not only because of more infections per generation but also because of faster generations. Further information about this research can be gained here. Archived

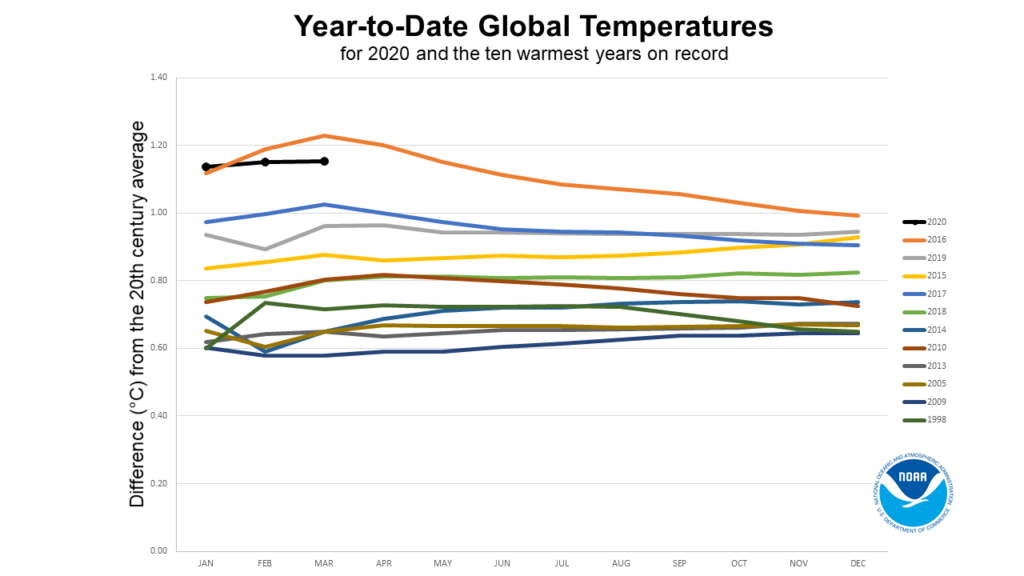

Moreover, when considering global warming, the increase in average global temperature is about 0.14° Fahrenheit (0.08° Celsius) per decade since 1880, but the rate of warming since 1981 is more than twice that: 0.32° F (0.18° C) per decade. 2021 was the sixth-warmest year based on National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) temperature data providing perfect breeding grounds for these disease-causing vectors.

Dengue population density tends to decline drastically during low precipitation and lower average temperatures in regions with tropical or subtropical climates, but it spreads rapidly when the conditions get reversed. And also, as the global temperature increases, mosquito dispersal can expand. Hence, containment of the spread in one place may lead to a rise elsewhere. More on this here, Archived.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has stated that human activities have already caused approximately 1.1 °C of global warming since the pre-industrial period, with each of the last four decades being successively warmer than any decade that preceded it since 1850. Moreover, the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report predicts that global temperature rise will reach 1.5°C and could be exceeded during the 21st century unless deep reductions in carbon dioxide (CO2) and other GHG emissions occur in the coming decades. More on this here Archived. Therefore, all regions of the world are at high risk of disease transmission.

National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) states that the environmental temperature experienced during the immature stages of mosquitos helps shape adult phenotypes. The ecological temperature in these immature stages selectively modifies adult mosquitoes’ traits related to virus transmission. Additionally, the NCBI study shows that the rearing temperature of immature stages affects adult mosquito interactions with the dengue virus, most likely attributable to alterations in viral replication and efficacy of the midgut escape barrier.

In contrast, the virus spread throughout the mosquito’s body, a prerequisite for transmission, was reduced when the immature stages were reared in cooler conditions. Read more about this phenomenon here.

The weather impacts the vector-borne illness dengue’s temporal and geographical spread. As a result, rainfall and ambient temperature are referred to as macro factors influencing dengue spread, directly impacting Aedes aegypti population density, as seen here. Archived

When considering extreme weather as a result of climate change induces dengue distribution, data collected from several research studies reiterate that dengue larval abundance is associated with increased rainfall and minimum temperatures.

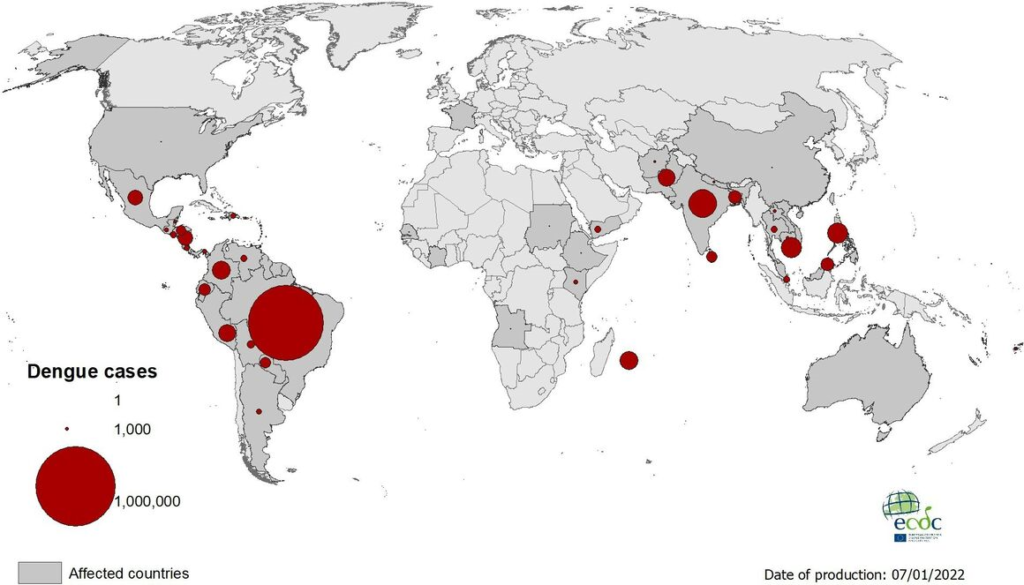

The Global Climate Risk Index 2020 analyzed to what extent countries and regions have been affected by impacts of weather-related loss (storms, floods, heat waves, etc.) The most recent data from 1999 to 2018 shows that Puerto Rico, Myanmar, and Haiti rank highest, as seen here Archived. When comparing dengue distribution, these countries ranked higher as well. According to Global Climate Risk Index, dengue was mainly reported in tropical climates before 2011. However, several dengue cases were recently reported in countries that do not lie close to the equatorial regions, as evident in the map below.

The dengue mosquito lays its eggs on the walls of water-filled containers. The eggs hatch when submerged in water. Eggs can survive for months; hence, with flash floods, more places are open for mosquitos to breed. Female mosquitoes lay dozens of eggs per sitting up to 5 times during their lifetime. Dengue causes a broad spectrum of diseases. This can range from subclinical disease (people may not know they are even infected) to severe flu-like symptoms in those infected. Although less common, some people develop severe dengue, which can be any complications associated with severe bleeding, organ impairment, and plasma leakage. Severe dengue has a higher risk of death when not managed appropriately. More can be read from here Archived.

The incidence of dengue has grown dramatically around the world in recent decades. Most cases are asymptomatic or mild and self-managed; hence, the actual numbers of dengue cases are under-reported. Many patients are also misdiagnosed with other febrile illnesses. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 3.6 billion people, or 40% of the world’s population, reside in dengue-endemic areas. Annually, an estimated 400 million people are infected with the dengue virus, 100 million become ill with dengue, and 21,000 deaths are attributed to dengue.

The number of dengue cases reported to WHO increased over eight-fold over the last two decades, from 505,430 cases in 2000 to over 2.4 million in 2010 and 5.2 million in 2019. Reported deaths between 2000 and 2015 increased from 960 to 4032, mainly affecting the younger age group. The total number of cases seemingly decreased during the years 2020 and 2021, as well as for reported deaths. However, the data is incomplete, and the COVID-19 pandemic might have also hampered case writing in several countries.

Signs of escalating climate change can no longer be ignored on any continent or region. Impacts from extreme weather events hit the poorest countries hardest as these are particularly vulnerable to the damaging effects of a hazard, have a lower coping capacity, and may need more time to rebuild and recover.

Therefore, it’s clear that extreme weather events resulting from human-induced climate change, such as significant summer rainfalls combined with sharp seasonal/temperature transitions, have caused substantially increased variability of runoff and its adverse effects on human populations, such as the spread of vector-borne diseases.

Comments are closed.

[…] dengue spread. The weather impacts dengue’s temporal and geographical reach. More can be read here. Flash floods also open more places for mosquitos to breed, leading to the spread of dengue, […]