Physical Address

23,24,25 & 26, 2nd Floor, Software Technology Park India, Opp: Garware Stadium,MIDC, Chikalthana, Aurangabad, Maharashtra – 431001 India

Physical Address

23,24,25 & 26, 2nd Floor, Software Technology Park India, Opp: Garware Stadium,MIDC, Chikalthana, Aurangabad, Maharashtra – 431001 India

Introduction

The urgency to combat climate change has brought attention to the preservation of natural carbon sinks, with wetlands emerging as crucial players in this global effort. In particular, vegetated coastal ecosystems (VCEs), known as “blue carbon” ecosystems, comprising mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes, have been recognized for their significant role in carbon capture and storage. Despite covering a small portion of the ocean surface, these ecosystems contribute significantly to carbon burial in marine sediments, thus playing a vital role in climate change mitigation.

Understanding Blue Carbon Ecosystems

Blue carbon ecosystems store vast amounts of carbon in their soils and biomass, with mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes collectively storing approximately 10 petagrams of carbon each in their top 1-meter soil layer globally. However, the carbon stocks vary widely depending on factors such as latitude, vegetation composition, hydrology, and anthropogenic influences.

Mangroves, resilient forests that thrive in harsh coastal conditions, are essential carbon sinks. They store the maximum portion of the carbon in their soils and biomass, making them invaluable in carbon sequestration efforts even compared to tropical forests.

Salt marshes, characterized by periodic inundation, exhibit rapid carbon burial rates, outpacing even tropical rainforests. Seagrass meadows, often overlooked but equally vital, provide essential habitat for marine life while sequestering carbon in their biomass and sediments. Their contribution to carbon storage underscores their importance in coastal ecosystems.

Source – What Is Blue Carbon and Why Does It Matter? – Sustainable Travel International

Blue Carbon in Sri Lanka: A Closer Look

Sri Lanka, blessed with a diverse coastline, harbors all three main types of blue carbon ecosystems. While mangroves dominate the coastal landscape, seagrass meadows and salt marshes also play significant roles in carbon storage. Despite their importance, comprehensive studies on carbon stocks in these ecosystems have been limited, with much of the focus historically placed on mangrove ecosystems.

According to 2022 data, the current area of the three habitats in Sri Lanka are as follows:

1. Mangrove Forests – The total area of mangrove forests in Sri Lanka is approximately 19,500 hectares.

2. Salt Marshes: The estimated total area of salt marshes in Sri Lanka is around 33,573 hectares which exceeds the total area of mangroves.

3. Seagrass Meadows: The area covered by seagrass meadows in Sri Lanka is approximately 23,819 hectares which reflects recent habitat loss.

As Sri Lanka seeks to address climate change and biodiversity conservation, bridging knowledge gaps regarding blue carbon ecosystems is critical. However, Sri Lanka’s mangrove extent, though considerable, faces threats from various anthropogenic activities, including land reclamation and aquaculture. Comprehensive studies are needed to assess carbon stocks accurately and guide conservation efforts. Salt marshes and seagrass meadows in Sri Lanka remain understudied, with limited data available on their carbon storage capacities. Comprehensive scientific surveys and research initiatives are needed to accurately quantify carbon stocks and inform policy decisions.

The biogeography and distribution of blue carbon habitats in Sri Lanka

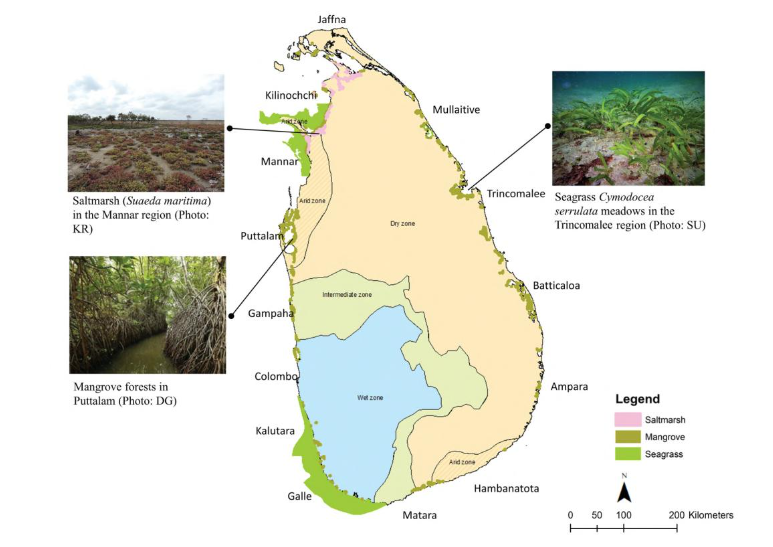

Figure 02: Distribution of blue carbon habitats in Sri Lanka

Source – Oceanography and Marine Biology: An annual review. Volume 60 – Google Books

These habitats’ distribution is influenced by various factors such as climate, oceanography, and geomorphology. Sri Lanka’s coastline stretches for approximately 1,750 kilometers and is characterized by a diverse range of coastal environments.

1. Climate Zones: Sri Lanka can be broadly divided into three main climate zones: the wet zone, the dry zone, and the intermediate zone. Mangrove forests are found all around the island and span the three climate zones, having a long.

2. Oceanography: Sri Lanka’s position in the equatorial Indian Ocean, with the Arabian Sea to the west and the Bay of Bengal to the east, results in biannually reversing monsoon winds. This oceanographic feature drives currents along the coast, affecting the distribution of marine habitats such as seagrass meadows.

3. Geomorphology: The coastal geomorphology, including factors like topography and tidal ranges, plays a crucial role in shaping the distribution of blue carbon habitats. Tidal ranges determine the landward penetration of seawater into tidal creeks and lagoons, influencing the extent of mangrove forests and salt marshes.

4. Biogeographical Patterns: The distribution of mangrove forests, salt marshes, and seagrass meadows varies across Sri Lanka’s coastline. Mangrove forests are found throughout the island, spanning the three main climate zones. Salt marshes are distributed predominantly in regions such as Mannar, Kilinochchi, and Jaffna. Seagrass meadows occur in various coastal areas but are particularly important in lagoons and shallow coastal waters.

However, it should be noted that, while the data on salt marshes and seagrasses are limited, salt marshes are often depicted in maps of individual studies, they have not been given a separate category in some coastal vegetation maps until recent years. Overall, the biogeography of blue carbon habitats in Sri Lanka reflects the complex interaction of climate, oceanography, and geomorphology, resulting in diverse and ecologically significant coastal ecosystems.

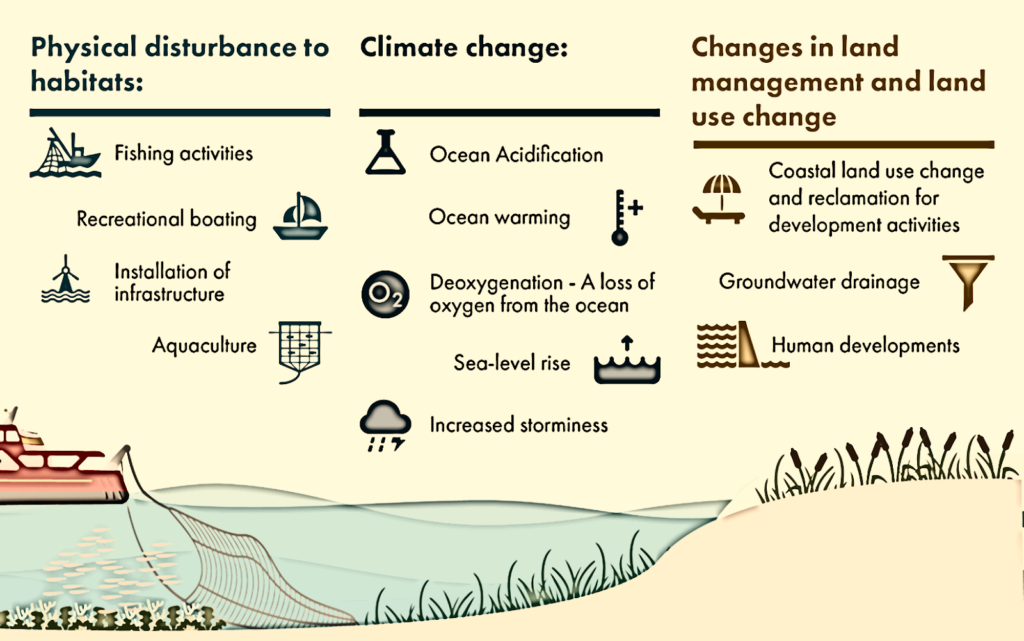

Anthropogenic Drivers of Blue Carbon Ecosystem Loss in Sri Lanka

1. Shrimp Farming Expansion

The rapid expansion of shrimp farming along the north-western coastline and in lagoons such as Chilaw and Negombo has been a primary driver of mangrove loss. This expansion, primarily focused on black tiger shrimp cultivation, has led to the conversion of coastal land into shrimp ponds, resulting in significant habitat degradation and biodiversity loss.

2. Urban and Industrial Development

The relentless pace of urbanization and industrialization has encroached upon Sri Lanka’s coastal areas, leading to habitat fragmentation and destruction. Infrastructure projects, including ports, harbors, and industrial zones, have altered coastal landscapes, displacing mangroves and salt marshes. Moreover, industrial effluents and urban runoff have introduced pollutants into coastal waters, further degrading ecosystem health.

Figure 03 – Drivers of Blue Carbon Ecosystem Loss

Source – Blue Carbon | Scottish Parliament

Current Status and Conservation Efforts

Despite implementing policies to prevent further mangrove clearance, including legal frameworks and regulations, enforcement remains a challenge. Several true mangrove species are at risk with two considered critically endangered (Ceriops decandra, and Lumnitzera littorea), three endangered (Bruguiera cylindrica (L.), Sonneratia alba, and Xylocarpus granatum)and five vulnerable (IUCN 2021).

While notable efforts have been made to restore lost mangrove forests, restoration initiatives for seagrasses and salt marshes have been limited in Sri Lanka. Addressing this disparity is crucial for comprehensive conservation strategies and the preservation of coastal biodiversity.

Enhanced remote sensing techniques and monitoring programs are needed to assess the extent and health of blue carbon ecosystems accurately. Comprehensive research on ecological functioning, carbon sequestration potential, and socio-economic value is essential. Moreover, community engagement in conservation efforts and sustainable resource management is critical for long-term success.

Conclusion

Blue carbon habitats in Sri Lanka represent invaluable assets in climate change mitigation and coastal ecosystem conservation. Anthropogenic pressures continue to threaten Sri Lanka’s blue carbon ecosystems. Urgent action is required to address the drivers of habitat loss, strengthen conservation measures, and fill knowledge gaps through robust scientific research and community engagement. Only through concerted efforts can Sri Lanka ensure the preservation of its invaluable coastal ecosystems and the vital ecosystem services it provides. Through collaborative research efforts and targeted conservation measures, Sri Lanka can harness the full potential of its blue carbon ecosystems, contributing significantly to global climate resilience.

With inputs from Nuwandhara Mudalige –